OneHundredCoffee is reader-supported, and some products displayed may earn us an affiliate commission. Details

If you’ve ever sipped two coffees from the same country and wondered how one tastes like ripe strawberries while the other leans into cocoa and spice, you’ve already discovered the magic of processing. It’s the period between picking the cherry and drying the seed (your coffee bean), and farmers have turned it into a creative playground. Around the world, producers are tinkering with fermentation times, yeast strains, oxygen levels, drying styles, and even temperature “shock” to unlock new flavors—all while trying to keep the cup clean, stable, and true to its origin. This is a behind-the-scenes story of how that happens, written in a friendly, real-world way that connects what farmers do on the patio to what you taste in your mug at home.

Let’s explore the most common (and the most experimental) approaches you’ll see on a bag label, what they mean for flavor, and how to choose brewing gear and beans to make those nuances sing.

Why Processing Matters More Than Most People Think

Think of coffee as a fruit-forward ingredient rather than a commodity. The seed inside the cherry is delicate, and what farmers do right after harvest shapes everything you taste later. Processing determines how much sugar, fruit esters, acids, and aromatic compounds migrate from the pulp and mucilage into the bean—and, crucially, how microbes transform those sugars. Even small changes in time or temperature can tilt the cup from bright and tea-like to jammy and dessert-like. That’s why the same farm can release radically different tasting lots from the same variety, picked on the same day.

For coffee growers, processing is equal parts science, artistry, and logistics. They’re managing fermentation like a winemaker, drying like a specialty tea producer, and quality-controlling like a chocolatier. They watch weather patterns, track pH and temperature, sniff fermentation tanks, and constantly taste. It’s passionate, hands-on work, and it’s also risky: a few hours too long under heat or a sudden rainstorm can introduce off-flavors that spoil an entire day’s harvest. When you pay a bit more for “experimental” coffees, you’re tasting all that effort and risk.

Washed (Wet) Process: Clarity and Structure

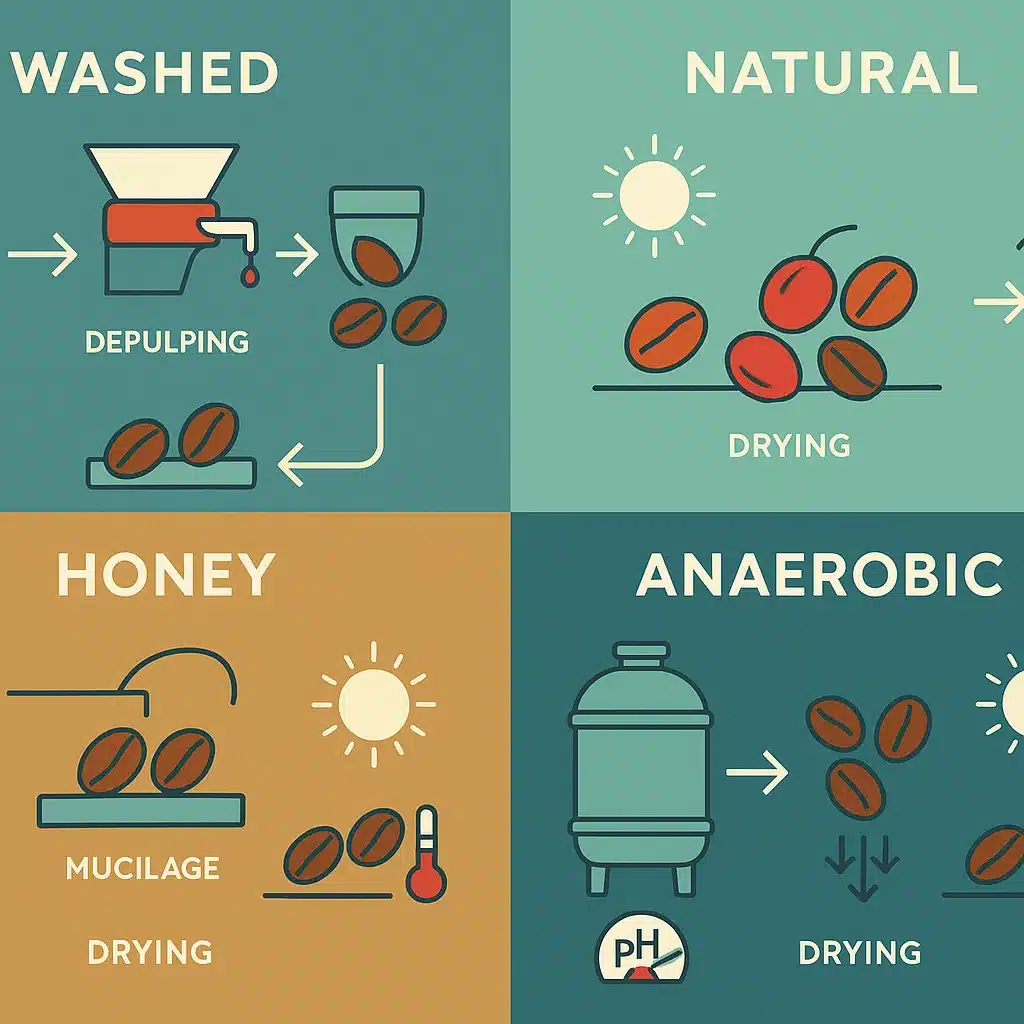

The washed process is the industry’s classical reference. Farmers remove the skin and most of the fruit from the cherry, then ferment the seeds in water to loosen any remaining mucilage before washing it away. The beans are then dried—on raised beds, patios, or mechanical dryers—until target moisture is reached.

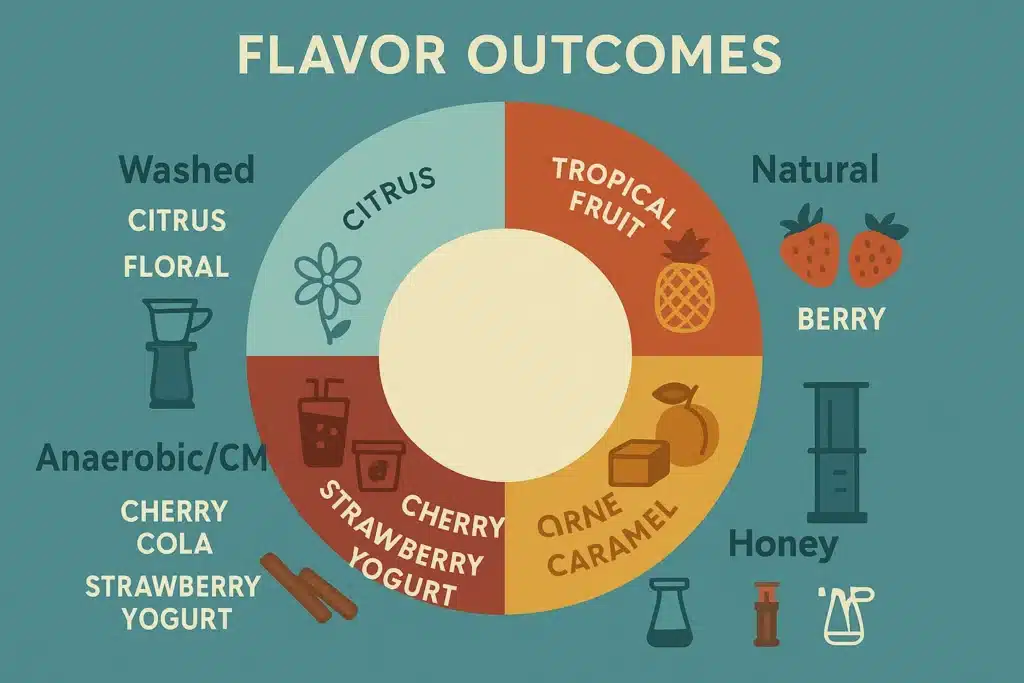

What you taste: cleaner, more transparent cups where acidity and varietal character shine. Think citrus, florals, and crisp stone fruit in East African lots; cocoa and cane sugar in many Central American washed coffees. If you like precision—flavors that feel well-defined and layered—the washed style is your comfortable home base.

What farmers tweak: fermentation time (short and cool for crispness, longer for deeper sweetness), water changes, pH monitoring, and even inoculating with specific yeast strains for consistency. Drying is just as crucial: slow, shaded drying tends to preserve brightness and extend shelf life; too-fast drying can flatten the cup.

Natural (Dry) Process: Fruit-Forward and Bold

With natural processing, ripe cherries are dried whole before the seeds are removed. The pulp and mucilage stay in contact with the seed for days or weeks, which allows sugars and fruit compounds to diffuse inside, while yeast and bacteria munch away and create new aromatics.

What you taste: saturated fruit—berries, tropical notes, jammy sweetness—plus bigger body. When done well, naturals taste like a fruit dessert. When mishandled, they can drift into fermented, boozy, or overripe territory. The line between “wow” and “whoa” is thin, and the skill of the processor makes all the difference.

What farmers tweak: meticulous cherry sorting (floats and underripes ruin clarity), drying curvature (starting slow to avoid splitting, finishing firm to stabilize), and frequent turning to prevent mold. Some producers dry on raised beds under parabolic greenhouse domes to buffer against rain and dew.

Honey (Pulped Natural): A Sweet Middle Path

Honey processing removes the outer skin but leaves varying thicknesses of sticky mucilage on the seed during drying. You’ll see “yellow,” “red,” or “black” honey on labels—roughly indicating how much mucilage stays on and how slowly the beans are dried.

What you taste: a bridge between washed clarity and natural fruit. Yellow honeys lean toward clean and citrusy; red honeys add berry sweetness; black honeys push toward dense, syrupy cups with dried fruit and chocolate. Honey lots can be wonderfully balanced for everyday drinking.

What farmers tweak: how much mucilage to leave on, shade versus sun exposure, and turning frequency. Too little airflow or too much moisture can cause wobbliness in flavor; done right, honeys glow with gentle fruit wrapped in caramel sweetness.

Anaerobic Fermentation: Flavor Through Oxygen Control

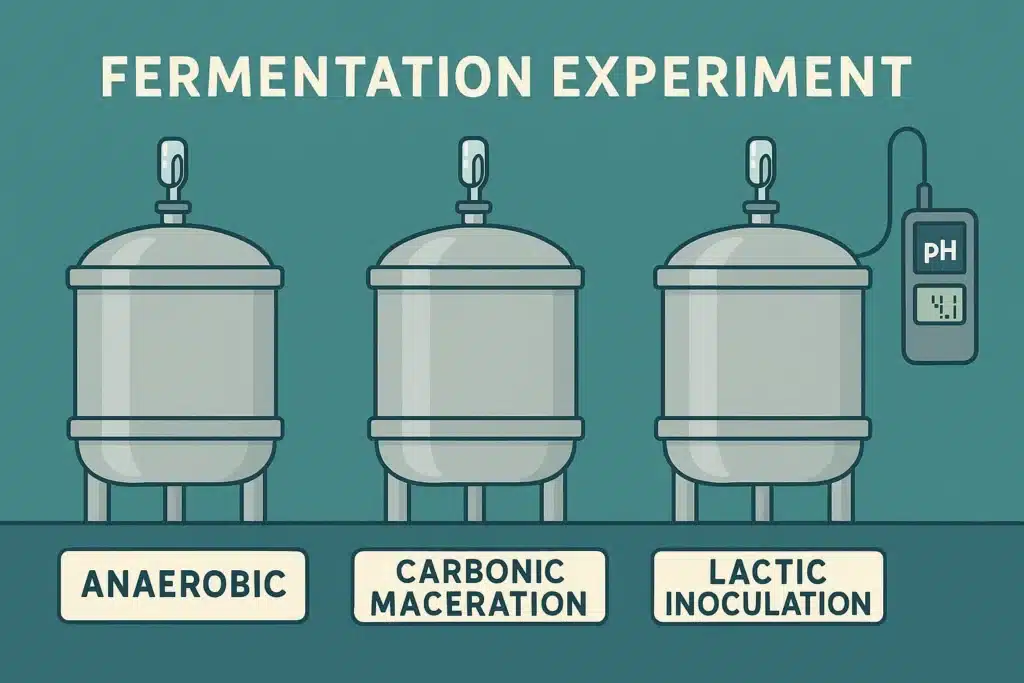

“Anaerobic” means fermentation in a closed or oxygen-limited environment—usually sealed tanks or bags, sometimes with airlocks to vent CO₂. Producers can do this with whole cherries, pulped cherries, or de-pulped parchment coffee. Oxygen control allows farmers to push fermentation further without the same risk of vinegar-like defects.

What you taste: heightened aromatics, candy-like sweetness, and sometimes a creamy, silky texture. Common notes include strawberry yogurt, cherry cola, tropical punch, and spiced mulled fruit. The best anaerobics remain clean and structured; the worst can taste perfumey or artificial. It’s a technique that rewards careful monitoring of pH, temperature, and time.

What farmers tweak: cherries vs. mucilage-on seeds, tank temperature (cool slows things down and preserves finesse), and fermentation duration based on pH drop. Some producers pre-dry cherries a day or two before sealing to concentrate sugars—a trick that adds intensity.

Carbonic Maceration: Borrowed From Wine, Brilliant in Coffee

Popularized in the specialty scene by forward-thinking producers, carbonic maceration (CM) involves placing whole cherries in a sealed tank, flushing with CO₂ to displace oxygen, and letting intracellular fermentation kick off. Because the cherries remain intact, enzymatic changes inside the fruit create striking, wine-like aromatics.

What you taste: elegant florals, candied fruit, baking spices, and a polished, almost glossy mouthfeel. It can taste like hibiscus spritz, pomegranate, and cinnamon sugar when dialed in. CM has become a competition darling because it’s both expressive and—when executed with discipline—surprisingly clean.

What farmers tweak: grape-style controls—CO₂ levels, temperature, and time—plus strict cherry selection to avoid any unripe fruit that could drag the cup down.

Lactic, Koji, and Cultured Yeast Fermentations: Microbial “Seasoning”

Here’s where the microbiology gets deliberate. Some producers inoculate tanks with specific lactic-acid bacteria to encourage a creamy, yogurt-like tang balanced by deep sweetness. Others dose with wine or beer yeasts to steer aromatics toward stone fruit, florals, or tropical esters. There are even experiments with koji (Aspergillus oryzae), a fungus used in sake and miso, to unlock enzymes that reshape sugars and proteins.

What you taste: layered sweetness, silky textures, and signature aromatics that feel “composed,” not chaotic. Lactic fermentations lean toward custard and dulce de leche; certain yeasts lift florals and white peach; koji experiments can produce umami undertones married to sweet fruit. These are advanced techniques that require careful sanitation and sensory checks to avoid overdoing it.

Double Washed, Extended Ferment, and Thermal Shock: Precision Tools

Some producers “double wash” or “double ferment”—briefly fermenting, washing, then fermenting again to refine texture and sweetness. Extended fermentations stretch timelines at controlled temperatures for sugar development without off-notes. Thermal shock alternates hot and cold water on fresh cherries or parchment to influence cell permeability, helping target compounds move more easily.

What you taste: a more sculpted cup—think of it as turning the treble, bass, and midrange knobs with a light touch. Done well, these techniques refine clarity and mouthfeel while preserving original character.

Drying: The Quiet Stage That Makes or Breaks a Harvest

Fermentation gets the headlines, but drying is the quiet hero. Farmers aim for a stable end moisture (typically around 10–12%) and lower water activity so green coffee can travel and store well. Too fast and the beans taste papery or hollow; too slow and they risk mold or phenolic taints.

Raised beds allow airflow above and below; parabolic dryers buffer weather swings; mechanical dryers—used carefully in stepped, low-temp cycles—can save a crop when the rainy season arrives early. Shade nets, frequent turning, and careful bed loading all matter. Drying is where great lots become shelf-stable and consistent.

Sustainability and Ethics: Experimentation With a Conscience

Creative processing should also be responsible processing. Experiments take water, energy, labor, and sometimes specialized equipment. Many farmers now recycle water from wet mills, compost cherry pulp as fertilizer, and use solar-assisted dryers to reduce their footprint. Paying fair premiums for successful experimental lots isn’t just good ethics—it’s an investment in the future of flavor. When you choose coffees labeled “experimental” or “limited fermentation,” your purchase signals that careful, quality-focused work is valued.

How to Choose Beans Based on Processing (and Taste What You Paid For)

Start with your flavor goals:

- If you love bright, layered clarity, look for washed Ethiopians, Kenyans, and high-grown Central Americans.

- If you crave ripe fruit and dessert-like cups, pick natural or red/black honey lots from Ethiopia, Costa Rica, or Brazil.

- If you want playful, perfumed aromatics, explore anaerobic or carbonic maceration lots from innovative producers anywhere in the tropics.

- If you’re a texture nerd, consider lactic or extended ferment coffees that trade on creaminess and round sweetness.

Then match the brew method. Washed coffees sparkle through pour-over (Hario V60, Kalita, Chemex). Fruit-forward naturals can be luscious in AeroPress or immersion brews that cushion acidity with body. Experimental anaerobics sing when you keep your brew clean, controlled, and well-ground (a consistent burr grinder matters more than almost anything).

Brewing for Clarity vs. Brewing for Fruit

You can nudge the same coffee in different directions just with water, grind, and method:

- For clarity (lean, sparkling cups): use a paper-filter pour-over at a slightly higher temperature (93–96 °C / 199–205 °F), grind a touch finer to lift extraction, and keep your ratio around 1:16–1:17. Agitate gently to avoid fines migration.

- For fruit-forward sweetness (jammy, plush cups): consider immersion or AeroPress at 92–94 °C / 198–201 °F, grind just a notch coarser, and lengthen contact time. A 1:15 ratio can enhance the body without going muddy if your grinder is consistent.

Water matters too. Moderate hardness and a bit of alkalinity help keep acids bright but not sharp. If you’re chasing precision, use a simple mineral recipe or bottled water formulated for coffee.

Storage: Protecting Those Delicate Aromatics

Experimental lots often peak when fresh and can lose their sparkle if stored poorly. Keep beans in an opaque, airtight container away from heat. If you buy multiple bags, consider splitting them into smaller containers and opening one at a time. For long-term protection, purging with an inert gas or freezing in well-sealed bags preserves aromatics. Thaw sealed to avoid condensation.

Real-World Tasting Roadmap: From “Interesting” to “Wow, I Get It”

If you’re new to processing-driven coffees, a simple tasting plan helps:

- Baseline with washed. Buy a washed Ethiopian or Guatemalan and brew it clean on a pour-over. Note the citrus, florals, or cocoa clarity.

- Contrast with a natural. Choose an Ethiopian natural from a reputable roaster and brew side-by-side. You’ll taste berry and tropical punch, with a thicker palate weight.

- Leap into anaerobic or CM. Pick a microlot labeled anaerobic or carbonic maceration and brew it with a meticulous pour-over. Note the perfumed, confectionery aromatics and silky texture.

- Try honey next. See how honey splits the difference—often cozy, caramelized sweetness with gentle fruit.

- Repeat with a different origin. Running the same sequence with, say, Costa Rica or Brazil, reveals how origin and altitude intersect with processing.

Keep notes, but in human language: “lemon candy,” “blackberry jam,” “rose and cinnamon.” The point isn’t scoring—it’s building a personal flavor map.

Troubleshooting: When an Experimental Coffee Tastes “Too Much”

Sometimes a cup edges into boozy, perfumey, or funky territory. That doesn’t mean the coffee is flawed, but it might need a gentler brew:

- Lower the brew temperature by 1–2 °C to soften volatiles.

- Coarsen the grind to avoid over-extraction of bitter phenolics.

- Shorten your contact time or reduce agitation to keep the texture silky.

- Try a different method—a paper-filtered pour-over often cleans up a cup that felt muddled in immersion.

If the coffee still tastes off (vinegar-like, musty, or medicinal), it may be mishandled or past peak. Reputable sellers will often help you troubleshoot or replace.

How Farmers Measure Success (and Why It’s Hard)

At origin, “success” isn’t only the cupping score. It’s repeatability, shelf stability, and paying the bills. Producers track:

- Cup quality over time: Does the coffee hold its flavor for months, or does it fade quickly?

- Defect rates: how often does a batch tip into ferment or phenolic taints?

- Labor and resource costs: extra turning on raised beds, water for washing, energy for dryers, and specialized equipment add up.

- Market response: Will roasters and drinkers pay a premium consistently for this profile?

When you see a farm repeat a certain process year after year, it’s because it ticks all of those boxes, not just because it tastes great in week one.

Editor’s Picks: 5 Amazon Finds to Taste Processing Differences

If you want an approachable, home-friendly lineup that showcases how processing changes flavor—and gear that helps you pull it out—these are excellent, widely available options on Amazon:

1) Volcanica Coffee — Ethiopia Natural (Whole Bean)

A classic, well-sorted Ethiopian natural that reliably delivers berry compote and florals without the “overripe” chaos. It’s a crowd-pleaser and an ideal starting point for natural processing.

Who is this for?

Volcanica’s Los Angeles Espresso Blend is perfect for coffee lovers who appreciate bold, deep flavors with a smooth crema. Crafted for espresso machines, it delivers a full-bodied experience with rich chocolate and nutty notes. Ideal for both home baristas and café-style brewing, this artisan roast satisfies refined and adventurous palates alike.2) Stumptown Coffee Roasters — Ethiopia (Seasonal Washed Lot)

Stumptown’s washed Ethiopians are known for clean citrus, jasmine, and stone fruit. Perfect for calibrating your palate to washed clarity before you explore anaerobics.

Who is this for?

Stumptown Holler Mountain is perfect for those who want a balanced, everyday organic coffee with full-bodied flavor. With creamy notes of caramel, citrus, and berries, it’s ideal for drip, French press, or espresso. Great for both newcomers and aficionados seeking a smooth, ethically sourced blend with a bright and sweet finish.3) Onyx Coffee Lab — Cold Brew or Seasonal Ethiopia (Washed/Experimental)

Onyx frequently offers washed and experimental Ethiopian lots. Their sourcing and roasting are meticulous, making them a great springboard into anaerobic or CM profiles without the risk of “too funky.”

Who is this for?

Onyx Coffee Lab’s Southern Weather blend is crafted for those who enjoy a sweet, balanced cup. With tasting notes of milk chocolate, plum, and candied walnuts, it’s ideal for daily drinkers who appreciate specialty-grade coffee. Great for pour-over, drip, or espresso lovers seeking harmony between fruity brightness and smooth richness.4) Hario V60 02 Dripper (Plastic or Ceramic)

Simple, inexpensive, and an industry staple for showcasing processing clarity. Pair with good filters and you’ll hear every note in the cup.

Who is this for?

The Hario V60 is for coffee enthusiasts who value control and clarity in every brew. Its spiral ribs and large single hole let you fine-tune flavor through pour speed and technique. Perfect for pour-over lovers seeking a lightweight, durable, and high-performing dripper that brings out vibrant, nuanced notes from fresh beans.5) Baratza Encore ESP (Conical Burr Grinder)

Uniform grind size is the foundation of flavor. The Encore ESP is approachable yet precise, helping both washed and natural coffees speak clearly without fines-driven muddiness.

Who is this for?

The Baratza Encore is for home brewers seeking professional-grade consistency and grind control. With 40 settings, it suits everything from French press to espresso. Quiet and reliable, it’s ideal for beginners and enthusiasts who demand uniform grinds for optimal flavor. Built to last, it’s a smart upgrade to any coffee setup.Use the washed Ethiopian with the V60 for a sparkling baseline, then brew the Volcanica natural in the same setup to taste the fruit swing. When you’re ready, slot in an experimental Onyx lot and pay attention to the perfume and texture.

Frequently Searched Questions—Answered Simply

Is anaerobic coffee safe?

Yes. It’s the same fermentation chemistry that underpins food like yogurt and wine, guided by farm hygiene and careful monitoring. Well-processed anaerobic lots are clean, stable, and delicious.

Does natural processing always taste fruity?

Often, but not always. Good naturals lean into berry and tropical notes, but a producer’s cherry selection and drying finesse can yield more restrained, chocolate-forward naturals too.

Which process is best for espresso?

All can shine. Washed coffees make articulate, structured shots; naturals add body and berry sweetness; anaerobics can be dessert-like. For milk drinks, naturals and lactic/extended ferment lots can be spectacular because their sweetness stands up to dairy.

What’s the easiest way to “taste processing”?

Brew a washed and a natural from the same origin back-to-back with the same recipe. Keep everything else constant. The contrast is unmistakable and incredibly fun.

Are experimental processes a fad?

They’re not going away. Techniques evolve (and some extremes will fade), but controlled fermentation and precise drying are now part of the specialty toolbox, much like temperature profiling is for roasters.

The Human Side: Why This Work Feels Personal

Behind every bag, a farmer is standing in gumboots on a drying patio, doing the slow, unglamorous work of turning coffee eight times a day. A producer is tasting tiny cups late into the evening to decide whether to end fermentation at hour 48 or 56. Families are betting on a new tank or a shade house because a roaster believed in their last experimental lot and paid a fair price. When you drink these coffees, you participate in that story—paying attention to flavor, celebrating craft, and supporting a feedback loop that rewards better, more sustainable practices.

I still remember the first time I brewed a washed Ethiopian and a natural Ethiopian side-by-side. The washed cup felt like a spring morning—lemons, white flowers, and clean air. The natural was summer at 4 p.m.—berries warmed by the sun, a little sticky, a lot of fun. Later, I tried an anaerobic lot that smelled like strawberries and cinnamon and couldn’t stop grinning at how playful it felt. Those moments changed how I shop and brew. They also changed how I read labels: not as marketing, but as breadcrumbs leading back to real choices on a real farm.

Putting It All Together: A Simple Plan for Your Next Month of Coffee

Week 1: Buy a washed coffee you trust and brew it on the V60. Dial it in until the cup is crisp and sweet.

Week 2: add a natural from the same region. Brew at the same ratio and note the texture and fruit.

Week 3: bring home an anaerobic or CM lot, keep everything constant, and decide how you feel about the perfume and silkiness.

Week 4: Try a honey to see how it stitches clarity to fruit. Swap one variable—grind size or temperature—each day and note how the cup moves.

By the end of a month, you won’t just know what you like—you’ll be able to explain why, in your own words, and choose beans and brew methods that echo those preferences. That’s real coffee literacy, and it’s surprisingly empowering.

Final Sip

Processing is how coffee farmers compose flavor—sometimes with classical instruments, other times with synthesizers and pedals. Washed offers a clean melody. Nature brings the chorus of fruit. Honey harmonizes the two. Anaerobic, carbonic maceration, and cultured fermentations layer in texture and perfume. Drying sets the groove that holds it all together.

When you choose beans (and gear) thoughtfully, you don’t just drink coffee—you listen to the producer’s composition as they intended it: balanced, expressive, and full of life. So pick a washed, a natural, and something experimental, brew them with care, and enjoy the lesson in the cup. The most exciting flavor lab in coffee isn’t in a big city café; it’s on a hillside where someone is watching the weather, turning cherries, and smiling because this year’s experiment tastes like sunshine.