OneHundredCoffee is reader-supported, and some products displayed may earn us an affiliate commission. Details

I still remember the first time I cupped two Ethiopians side by side—same harvest, same region, same roaster—one a classic washed lot, the other a natural, fruit-splashed experiment. The natural tasted like strawberry jam had been sun-kissed on the rim of the cup. The washed felt like jasmine and lemon peel drifting through clean spring water. Same coffee plant, wildly different cups. The invisible artists behind those differences? Yeasts and microbes work quietly during fermentation.

Coffee connoisseurs who enjoy complex flavor layers and rare, exotic fermentation profiles.

Specialty coffee enthusiasts looking for exclusive micro-lots and traceable farm-to-cup quality.

If you’ve ever wondered why a “natural” coffee can taste like a fruit salad, why some lots feel silky while others sparkle, or what “anaerobic” honestly means on a bag label, this deep dive is for you. We’ll keep it friendly, practical, and grounded in real-world tasting and farm-floor reality—so you can map what’s happening with microbes to what you’re tasting in your mug.

What “Fermentation” Actually Means in Coffee

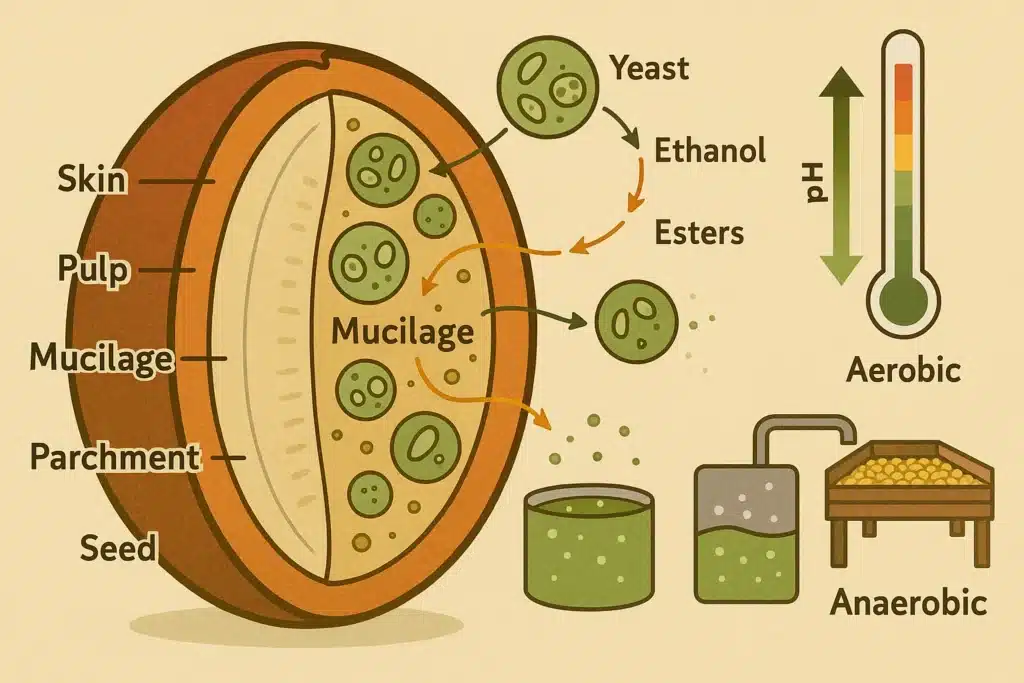

In coffee, “fermentation” is the stage where microbes—mainly yeasts and bacteria—consume sugars and other compounds in and around the coffee seed (what we roast), especially within the sticky mucilage layer that clings to the parchment after depulping. This stage happens between picking and drying. Depending on the processing method, it can occur with or without the fruit skin, in tanks or bags, under oxygen or with limited oxygen, and for short or long periods.

Why do we do it? Two big reasons:

- Practical: Fermentation helps break down the mucilage so the parchment can be washed clean (in washed coffees) or so the fruit dries more efficiently (in honey and natural coffees).

- Sensory: Fermentation changes the chemistry of the seed, shaping the final aroma, acidity, sweetness, and mouthfeel. Think of it as nudging the coffee’s raw ingredients toward a flavor direction—bright and floral, plush and tropical, creamy and lactic, spice-tinged, cocoa-rich, and on it goes.

Coffee isn’t fermented like wine or beer (you’re not drinking fermented juice directly). Instead, fermentation is one step in the post-harvest journey that influences how the green seed roasts and brews.

Meet the Microbial Cast: Yeasts, Bacteria, and Friends

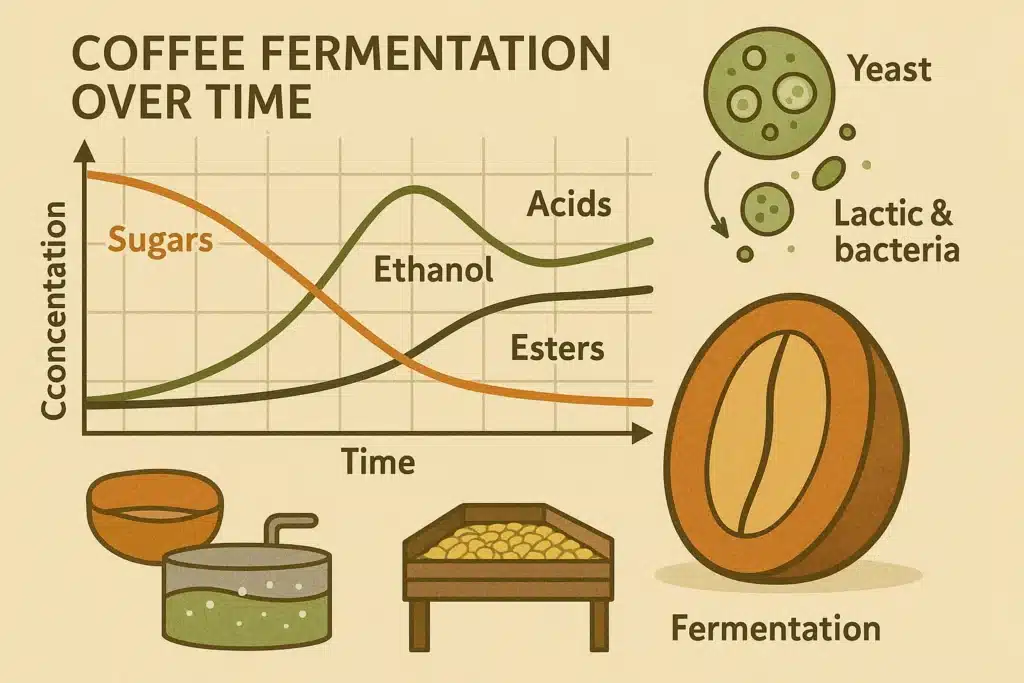

There isn’t a single microbe “in charge.” There’s a community—different species rise and fall depending on sugar availability, temperature, oxygen levels, time, and water activity.

Yeasts (the flavor painters)

Yeasts are usually the first to get going. They thrive on sugars from the mucilage and, in natural process coffees, the fruit pulp. You’ll often hear about Saccharomyces (famous from wine and beer) and non-Saccharomyces genera like Hanseniaspora, Pichia, Candida, Metschnikowia, and Kluyveromyces. Each group brings a slightly different toolbox of enzymes and metabolic byproducts.

- Aromatics & esters: Many yeast strains tend to produce fruity esters and floral volatiles—things we perceive as berry notes, stone fruit, tropical touches, or perfumed florals.

- Mucilage breakdown: Yeasts (and some bacteria) produce enzymes that help degrade pectins and polysaccharides, making the sticky layer easier to remove or dry.

- Texture & sweetness: By modifying sugars and producing glycerol and other compounds, yeasts can influence perceived body and sweetness in subtle ways.

Lactic Acid Bacteria (the polishers)

Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc (and cousins) are the lactic acid bacteria you often hear about in “lactic fermentation.” They generally love low-oxygen conditions and munch on sugars to produce lactic acid.

- Acidity: Lactic acid reads softer and rounder than acetic acid; it can add a creamy, yogurt-like brightness and smoothness.

- Structure: When lactic acid keeps pH within a favorable range and is managed well (temperature, time), the cup can feel polished, clean, yet plush.

Acetic Acid Bacteria (the sharp-tuners)

Acetobacter and others lean toward oxidizing alcohol to acetic acid (vinegar). In tiny amounts, they can add lift. In unmanaged conditions, they tip the cup into harsh, vinegary territory.

- Risk & reward: Some of the vivid “pop” in a lively coffee traces to subtle acetic contributions—too much, and it’s astringent and biting.

Other Microbes

Depending on the farm and method, you’ll find other bacterial and fungal species. Not all are beneficial; some can lead to defects (phenolic, moldy, onion/garlic, “over-fermented”). Good producers control the environment to favor a beneficial succession: yeasts early, lactic bacteria shaping acidity, minimal uncontrolled acetic activity.

Processing Methods and How Microbes Behave

Washed (a.k.a. wet process)

Cherries are depulped, leaving the sticky mucilage on the parchment seeds. The seeds rest—often submerged or in tanks—until the mucilage loosens. Then they’re washed and dried.

- Microbial play: Yeasts start, lactic bacteria continue, all usually in a more controlled, aqueous environment.

- Cup profile: Clean, floral, citrus, tea-like clarity; acidity can be gentle or sparkling depending on time and temperature control.

Honey (pulped natural)

Cherries are depulped, but much of the mucilage stays on while the seeds dry. “White/Yellow/Red/Black honey” usually refers to how much mucilage remains and how slowly it dries.

- Microbial play: Yeasts are more involved during drying; oxygen exposure is higher than in submerged tanks.

- Cup profile: More body and fruit sweetness than washed, with varying clarity depending on drying speed and cleanliness.

Natural (dry process)

Whole cherries are dried with the fruit intact. Fermentation begins inside the fruit and around the seed during the drying period.

- Microbial play: Yeasts flourish early thanks to abundant sugars; bacteria join and contribute as conditions change.

- Cup profile: Big, fruit-forward aromatics—berries, tropicals, jammy sweetness—if well-managed. Poor management shows as boozy, harsh, or overripe notes.

Anaerobic, Carbonic Maceration, and “Lactic”

These are refinements that tweak oxygen levels, vessel type (sealed tanks, grain-pro bags), and some even add CO₂ (carbonic maceration), and target specific outcomes.

- Anaerobic: Limiting oxygen favors yeasts and lactic bacteria. You often get rounded acidity, deep fruit, and creamy textures. Mismanaged anaerobic processes can taste “pickle-y,” solvent-like, or overly funky.

- Carbonic maceration: Borrowed from wine; whole cherries in CO₂-rich environments. Expect flamboyant aromatics—rose, tropicals, bubblegum—when properly executed.

- “Lactic”: Usually means conditions favor lactic bacteria. Think silky mouthfeel, dulce de leche sweetness, soft acidity—best when the pH, temperature, and time are dialed in.

How Farmers Steer Fermentation Toward Flavor

A well-run fermentation isn’t guesswork; it’s a craft. Here’s how producers nudge microbes toward desirable outcomes:

- Fruit ripeness: Riper cherries mean more sugars for yeasts and bacteria, leading to richer aromatics—too ripe risks unwanted microbes and off-notes.

- Sorting & cleanliness: Removing floaters and underripes, keeping tanks clean, and using fresh water when needed helps the “good” microbes win.

- Temperature: Warm conditions speed up fermentation; cooler nights slow it down. Many producers aim for a moderate pace to avoid spikes in acetic acid and volatile faults.

- Time: Some lots shine at 12–24 hours, others at 48–72+ hours. Longer isn’t automatically better; it’s about what the coffee wants. Some anaerobics run much longer, but at carefully controlled temperatures.

- Oxygen management: Open tanks vs sealed vessels vs submerged fermentation, all change, which microbes dominate?

- Inoculation vs spontaneous: Some producers add a selected yeast culture (inoculation) for repeatability; others rely on native microflora for terroir-driven uniqueness.

When these variables line up, you get that dazzling, distinct cup that feels hand-signed by the farm.

Why Some Fermented Coffees Taste “Too Funky”

We’ve all met a coffee that promised “anaerobic berry sundae” and delivered “hot sauce and nail polish.” What went wrong?

- Uncontrolled acetic spike: Excess oxygen during a long fermentation can boost acetic acid bacteria, leading to vinegar sharpness.

- Temperature highs: Hot ambient temperatures can accelerate pathways that overproduce solvent-like volatiles.

- Poor cherry selection: Overripe or damaged cherries invite spoilage microbes that paint over delicate flavors with rough strokes.

- Dirty infrastructure: Old residues in tanks or on patios can seed off-flavors.

Good producers keep logs, measure pH and temperature, adjust batch sizes to ambient conditions, and taste their coffees constantly throughout the harvest to refine their approach.

The Chemistry (Without Pretension)

You don’t need a lab degree to connect chemistry to flavor. A few simplified, useful ideas:

- Sugars → Acids & Aromatics: Microbes eat sugars and produce organic acids (lactic, malic, acetic) and volatile compounds (esters, aldehydes, higher alcohols) that shape aroma and perceived acidity.

- Enzymes → Texture & Clarity: Microbial enzymes break down pectins and complex polysaccharides, affecting how the seed dries and later how the brewed coffee feels—sleek, syrupy, or crisp.

- pH & Redox: Lower pH (more acidic environment) can preserve brightness and rein in spoilage. Oxygen availability (redox) steers which microbial pathways dominate.

When roast and brew unlock those compounds, you taste the story.

How Roasters Respond to Fermented Lots

Roasters quickly learn that an aggressively fruit-forward anaerobic coffee doesn’t roast like a gentle washed bourbon.

- Charge & momentum: Many roasters choose a slightly gentler initial approach to preserve delicate esters in intense anaerobic lots, avoiding too much early heat that can mute florals and fruit.

- Development: Pushing development time too far can caramelize away the sparkle in a lactic or carbonic maceration coffee. Too little can leave a green snap under the fruit. Sweet spot hunting is real.

- Rest time: Some microbial-forward coffees benefit from an extra day or two of rest to let aromatics knit together and volatile spikes soften.

If you buy whole beans, don’t be surprised if a roaster’s recommended brew window is a touch later for the wildest fruit bombs.

Brewing to Highlight Microbial Magic

You can absolutely “aim the spotlight” on fermentation-driven flavors at home.

- Pour-over for clarity: Hario V60, Kalita Wave, and Chemex tend to present florals, citrus, and delicate esters clearly. Use medium-fine grinds and keep your bed thin and even.

- Immersion for texture: French press or cupping-style immersion softens edges and elevates body, often perfect for lactic-leaning coffees.

- AeroPress for balance: Short immersion + pressure can bring out round sweetness without losing too much top-end fruit.

- Water matters: If your water is very hard or very soft, consider a brew water recipe. Balanced alkalinity and hardness keep acidity lively but not sharp.

- Grind distribution: A consistent grinder pays dividends; fewer fines mean less muddiness and brighter, more defined fruit.

Tweak one variable at a time—grind, ratio, temperature—so you can feel what each change does to the microbial “accent” in your cup.

Choosing Fermented Coffees You’ll Actually Love

With labels boasting “natural,” “honey,” “anaerobic,” and “carbonic,” it can feel like you need a decoder ring. Here’s a helpful mindset:

- Start with washed vs natural: If you love jasmine, bergamot, and lemonade, washed Ethiopians and Kenyans are happy places. If you swoon for strawberry jam and mango, naturals from Ethiopia or Brazil are calling.

- Then try honey: Split the difference—more body and sweetness than washed, cleaner than many naturals.

- Then explore anaerobics: Start with a roaster you trust. Look for sensory words like “creamy,” “red fruit,” “chocolate mousse,” and tropical punch.” Avoid descriptors like “balsamic” or “funky” at first if you’re not sure you want that.

- Country cues: Ethiopia and Yemen naturals often mean florals plus berries; Brazils tend to be nutty, chocolate-forward, but can be wildly fruity in certain naturals; Colombias are experimentation playgrounds—washed clarity, honey sweetness, and anaerobic fireworks all coexist.

Storing Microbial-Forward Coffees

Those electric aromatics can fade if you store beans carelessly.

- Air, light, heat, moisture: Keep beans in a one-way valve bag or an airtight container away from sunlight and heat sources.

- Freeze for freshness: If you won’t finish a bag within two to three weeks, portion it into airtight containers or freezer bags. Grind straight from frozen—many pros do it to preserve volatile compounds.

- Avoid humid kitchens: Moisture is the enemy of crisp aromatics.

Microbial Terroir: Why Place Still Matters

Even with the same yeast strain added, a farm in Huila won’t taste like Hambela. Native microbial communities still interact with inoculated cultures. Soil, altitude, day–night temperature swings, and water all nudge the microbial succession in their own way. That’s why terroir remains an anchor: processing is a lens, not a paint-over.

Quality & Safety: The Unseen QA

Good mills monitor pH, temperature, and time. They keep tanks clean, dry coffee quickly to safe moisture, and store parchment properly to avoid mold. All this matters for cup quality—and your peace of mind. The take-home for buyers is simple: buy from reputable roasters who source from producers that run tight ships. If a coffee tastes stinky, harsh, or oddly chemical, trust your palate and move on.

My First “Lactic” Eye-Opener

On a sourcing trip, I tasted a small-batch Colombian “lactic” lot side by side with the farm’s classic washed. The washed sang with lime-zest brightness and cane sugar. The lactic version felt like the same melody wrapped in velvet—silky, dulce de leche sweetness, a softer light around the edges. It didn’t replace the washed; it reinterpreted it. That’s the joy here: fermentation isn’t a fad, it’s a palette for expression.

Troubleshooting Your Cup: When Fermentation Shows Up Weird

- Tastes like vinegar: Grind coarser, lower water temp slightly, and shorten brew time. If it remains sharp and thin, the coffee may be over-fermented; try immersion for body or switch beans.

- Flat and muddled: Finer grind or clearer filter (paper over metal) can snap flavors back into focus. Check your water—very high alkalinity can smother delicate esters.

- Too “funky”: Extend your rest time after opening (some anaerobics calm down on day 5–7). Try lower brew temps (90–92°C) to trim solvent-like edges.

The Future: Precision Fermentation Without Losing Soul

We’ll see more controlled tanks, selected yeast inoculations, and sensor-driven fermentation, especially as smallholders chase premiums. The best versions will keep the coffee’s place and variety in the driver’s seat, with microbes as creative copilots. The goal isn’t to make every coffee taste like strawberry yogurt; it’s to let each origin explore new dialects of its native language.

FAQ-Style Answers to Common Google Questions

Is coffee fermentation safe?

Yes—when producers manage time, temperature, cleanliness, and drying, fermentation is a standard, safe step. Reputable roasters source from mills that rigorously control these variables, and final roasts are dry and stable.

Does fermentation make coffee alcoholic?

No. Any alcohols produced during fermentation are trace-level intermediates and don’t carry over into the roasted, brewed cup in intoxicating amounts. You’re tasting the aroma, not drinking wine.

What’s the difference between anaerobic and washed?

“Washed” describes how mucilage is removed and the overall cleanliness/clarity of the cup; it usually involves a shorter, oxygen-present or submerged fermentation and thorough washing. “Anaerobic” describes oxygen-limited conditions during fermentation (sealed tanks, bags). You can have an anaerobic “washed” or “natural”—anaerobic is about oxygen control, not whether fruit is present during drying.

Why do natural coffees taste fruity?

Because the seed dries inside the fruit, yeasts have more sugar to metabolize, producing a flush of fruity, floral aromatics that remain associated with the seed. Good naturals taste like fresh berries; poor naturals taste boozy or overripe.

What does “lactic fermentation” taste like?

Rounder, creamier acidity—think yogurt-smooth brightness. Often paired with caramel, dulce de leche, or milk-chocolate sweetness when executed well.

Are inoculated yeasts better than wild fermentation?

Neither is inherently “better.” Inoculated yeasts boost consistency and repeatability; spontaneous fermentation can express local microbial terroir and surprise you (for better or worse). The producer’s skill matters most.

How long should fermentation last?

It depends on temperature, cherry ripeness, and the method. Some washed coffees are ready in under 24 hours; some anaerobic naturals go 72 hours or more under controlled conditions. Time is a tool, not a trophy.

A Taster’s Map: Connecting Process to Flavor at a Glance

- Washed → Clarity, florals, citrus, tea-like elegance

- Honey → Rounder body, honeyed sweetness, balanced fruit

- Natural → Big berry/tropical notes, jammy sweetness, potential wildness

- Anaerobic (any) → Intensified aromatics, creamy or perfumed, can be flamboyant

- Carbonic maceration → Perfumed, playful, sometimes confectionary or “bubblegum”

- Lactic → Silky, mellow acidity, dessert-like sweetness

Use this map when you’re shopping and when you brew. If your wash tastes murky, try a cleaner brew method or filter. If your anaerobic feels too loud, drop the brew temp or switch to immersion to smooth it out.

Practical Home Experiments (No Lab Gear Needed)

- Two Ethiopians, three brewers: Brew a washed and a natural in V60, AeroPress, and French press. Notice how each brewer amplifies or trims different fermentation notes.

- Temperature ladder: Take one anaerobic coffee and brew three cups at 90°C, 93°C, and 96°C. The lowest temp often softens solvent-like edges; the highest lifts florals but risks sharpness.

- Freeze half the bag: Cup fresh vs two-weeks-frozen side by side. Frozen beans usually keep those delicate esters more intact, especially in floral and fruity coffees.

Keep notes; your palate is a muscle that gets stronger with reps.

Respect for the Craft (and Why It Matters)

Behind every “wow” cup is a producer making dozens of judgment calls: when to pick, how to sort, how long to ferment, whether to seal the tank, when to wash, how to dry, how to store. Yeast and microbes are powerful, but they need a conductor. When you pay a few dollars more for a carefully fermented coffee, you’re not just buying a flavor—you’re funding the skill and risk management that made it possible.

Final Sip

Yeast and microbes are the quiet collaborators in your favorite coffees. They soften edges, paint in aromas, and add depth to sweetness. They can turn a familiar variety from polite citrus to a bowl of peaches, or from cocoa nibs to chocolate mousse. But they don’t erase origin; they interpret it. Once you start listening for their signatures, your coffee world gets bigger and more delicious.

So pick up a clean, washed, and joyful natural, maybe a honey and a gently handled anaerobic, and brew them with intention. Taste the difference microbes make—and you might find your new favorite way to drink a place, a harvest, and a farmer’s judgment in every cup.